'Montjoie!': Macron takes a royalist slap in the face for the Republic

The man accused of slapping the French president on the face this week is to appear in court on Thursday. He shouted “Montjoie! Saint Denis” as he delivered the blow. The expression is rooted in France’s far-right monarchist Action Française, which has a history of trying to beat the Republic into shape.

Issued on:

Ahead of regional elections and next year’s presidential polls, President Emmanuel Macron is eager to get closer to the people. But he got a little too close on Tuesday when his bid to shake hands on a walkabout in the Drôme met with a slap in the face.

Video footage showed a young, long-haired man in a green tee-shirt shouting “Montjoie Saint Denis! A bas la Macronie” (down with Macronie) and then slapping Macron’s left cheek.

Emmanuel Macron giflé: un témoin BFMTV filme l'agression d'un autre angle pic.twitter.com/mP907RtTki

— BFMTV (@BFMTV) June 8, 2021

The suspect, 28-year old Damien T., and his friend Arthur C., were subsequently taken into custody for “violence against a person in authority”.

As authority goes, you can’t aim much higher than the president himself.

Macron tried to minimise the event telling the Dauphiné Libéré daily on Tuesday that it was an “isolated” incident committed by “ultraviolent individuals”.

But Prime Minister Jean Castex adopted a graver tone. "Through the head of state, it is quite simply democracy that is targeted. I call for a republican awakening, we are all concerned," he told the National Assembly.

Damien T. is to appear in court on Thursday. Investigators have found a number of fake weapons at his home, his social media accounts show an interest in Medieval role play, royalism and the far-right.

Violence in the service of reason

The cry of “Montjoie! Saint Denis!” merits attention.

It was first used in the 12th century as a royalist war cry, but gained popularity outside monarchist circles thanks to the 1993 cult film “Les Visiteurs” which might loosely be described as France’s answer to Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

Whether Damien T. and Arthur C., who face up to three years in prison and a fine of €135,000, were more influenced by medieval history or a cult French film is the work of investigators. But both the expression and the slapping constitute a political act rooted in the far-right, royalist, anti-Semitic Action Française movement, says centrist politician Jean-Louis Bourlanges.

He recalls the emblematic song Les Camelots du roi (The King's Camelots) which is set around the refrain “Long live the King, down with the Republic!/Long live the King; the wench we will hang!”

“But there’s another couplet in there,” Bourlanges told RFI, “Long live Lucien Lacour/He slapped Briand one day.”

It references a historical event in 1910 when Lucien Lacour, a member of the Camelots du roi, slapped the republican and radical-socialist Aristide Briand in Paris's Tuileries gardens.

“Briand wasn’t president of France but he was president of the Council several times and the far-right Action Française celebrated the fact he was slapped,” Bourlanges said.

Briand was inaugurating a monument to Jules Ferry, the founder of French, secular, public school, when he was struck, so Lacour gave the Republic a double whammy: Briand as the embodiment of the authority of the state and Ferry as the founder of secular education.

During his trial, Lacour defended his ideological position saying: “Briand represented for me the law of separation…which offended my Catholic conscience. He also represented the republic and Jules Ferry, who had driven God out of school and put Protestants at the head of public education. In the name of the patriots, in the name of the Catholics, I wanted to mark Briand's face.”

When asked why he acted the way he did, he replied: “Because our doctrine is violence in the service of reason.”

Striking the president

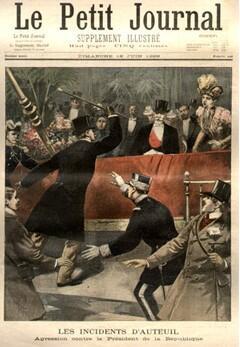

Bourlanges highlights another “more serious” example of physical violence against people in authority. In June 1899, at the height of the Dreyfus affair, President Emile Loubet was struck with a cane during a visit to a racecourse in the west of Paris.

“Loubet was a Dreyfusard, and had pardoned [the Captain],” making him an enemy for the anti-Dreyfusards.

A crowd of young royalists and members of anti-Semitic groups organised a kind of happening to humiliate the president. Among them was Baron de Christiani, “who was surrounded by people from the far-right”. He promptly brought his heavy cane down on the president’s head, squashing his hat.

The incident sent shock waves throughout the media. “It is difficult to understand why young people from good society would demonstrate, boo and even attack a 60-year old man with a cane, not least when he was surrounded by many foreign ambassadors,” wrote Le Figaro on 5 June 1899 in an editorial.

A far-right tradition

In 1936, the Camelots du roi made another attempt to "redress" the Republic when they lynched MP Léon Blum, shortly before he became prime minister. Blum, a Jew, was dragged from his car and beat almost to death. The Action Française newspaper described him as “the circumciser of Narbonne".

The savage attack prompted MPs to finally dissolve both Action Française – which Lacour presided for a while – and its Camelots du roi henchmen.

Given “there is this far-right tradition” of attacking symbols of authority, Bourlanges says it comes as no surprise that Marine Le Pen, leader of the hard-right National Rally, was so quick to denounce the Macron slap as "utterly unacceptable".

“Marine Le Pen was altogether right, in terms of serving her own interests, to dissociate herself immediately and brutally from what could have been assimilated to her policies,” he says.

The risk of getting too close

The Macron slap is just the latest in a series of swipes at French politicians.

On the Bastille Day parade in 2002, far-right activist Maxime Brunerie tried to assassinate president Jacques Chirac on the Champs-Elysées. In the same year, the mayor of Paris, Bertrand Delanoë was stabbed by a mentally unstable man in Paris.

In 2011, President Nicolas Sarkozy was grabbed by the shoulder and nearly knocked to the ground on a visit to Brax. Former prime minister Manuel Valls was slapped during campaigning for the left-wing primary in early 2017.

Also in 2017, the candidate for the legislative elections in Paris Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet was pushed around in a market.

“Relations in our society are strained,” political scientist Olivier Rouquan told RFI. “Over the last 20 years or so there is growing anger and distrust of politicians. It’s a kind of divorce, part of the population is rejecting the political class.”

Such resentment and rejection of the political class has been epitomised in France's Yellow Vest movement, and a few of those hi-vis jackets could be seen during this week's presidential slap. Damien T. told investigators he sympathised with the movement.

Politicians are not helping matters by trying to cosy up to the public, Rouquan says.

“They are increasingly using a form of communication based on the idea that they resemble the people. So when they’re in the crowds, the public tend to talk to them as if they were neighbours. It’s a risk.”

In the run up to regional elections at the end of June, and presidential polls next May, the temptation to reach out to the crowds is increasing – and with it, the risk of getting slapped.

Daily newsletterReceive essential international news every morning

Subscribe